Quantum Mechanics for Quantum Computing

This issue was written by guest editor Brent G. Hunsaker, a Senior Staff Engineer at Northrop Grumman with a degree in physics.

History of Quantum Computing

Early History

Richard P. Feynman

One of three of the first to conceive of the quantum computing idea was Richard P. Feynman, one of the scientists on the Manhattan Project developing the atomic bomb. After WWII Feynman held a tenured professorship at Cal Tech and wrote two articles titled: “Simulating Physics with Computers” published in the International Journal of Theoretical Physics 21 (1982), 467-488, and “Quantum Mechanical Computers” published in the Foundations of Physics 16 (1986), 507-531. His article “Quantum Mechanical Computers” was also published in Optics News 11(2), 11-20 (1985). In addition, Feynman also published a book titled “Feynman Lectures on Computation” published by Westview Press, July 7, 2000. Feynman Lectures on Computation, Chapter 6.3 “A Quantum Mechanical Computer”, 191-199, Westview Press, 1996.

Paul Benioff

Paul Benioff described a quantum model of Turing machines in 1980 and published “Computer as a physical system: a microscopic quantum mechanical Hamiltonian model of computers represented by Turing Machines.”, J. Stat. Phys.; (United States) 22:5, 525-532 (1 1980)

Yuri Manin

Manin published the book “Computable and Uncomputable” in 1980. The book was published in Russian and only translated to English years later.

“Feynman noted that although a classical computer can simulate the behavior of an n-particle system that evolves according to the laws of quantum mechanics, such simulation is inefficient and needs exponential time and space. Feynman’s call to action was to regard the particles themselves as a quantum computer that appears to be exponentially more efficient. [1]”

“Driven by a desire to realize Feynman’s vision of great computational power major efforts have been devoted to building quantum computers.” Today we are seeing quantum computers with over 2000 qubits driving to multi-million qubits.

David Deutch

David Deutch showed how quantum gates can function like classical logic gates. In 1985 he published “Quantum Theory, the Church-Turing principle and the universal quantum computer” in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series A 400, 1818 (July 1985), 97-117. He also published in 1989 “Quantum Computational Networks” in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences 425, 1868 (1989), 73-90.

Deutch kicked off the development of quantum computing with these two articles describing a framework for quantum computing. He developed and refined a generalized algorithm for quantum computing with Richard Jozsa.

An excellent book with a more detailed history of Quantum computers is titled: “Quantum Computing: An Applied Approach, Chapter 2, A Brief History of Quantum Computing, P16-21” by Jack D. Hidary.

Defining a Quantum Computer

How is the quantum computer constituted? Hidary’s book describes David DiVincenzo’s outline for the key criteria of a quantum computer. A quantum computer has the following key requirements:

- A scalable physical system with qubits that are distinct from one another.

- The ability to initialize the state of any qubit to a definite state in a computational basis.

- The system’s qubits must be able to hold their state.

- The system must be able to apply a sequence of unitary operators to the qubit states.

- The system can make “strong” measurements of each qubit.

According to Jack Hidary, “A quantum computer is a device that leverages specific properties described by quantum mechanics to perform computation.” Hidary, Jack D., Quantum Computing: An Applied Approach (p. 3). Springer International Publishing. Kindle Edition.

Unlike classical computers that rely on bits representing either 0 or 1, quantum computers utilize qubits as the basic units of information.

Here’s how this translates into the constitution of a quantum computer according to Hidary’s perspective:

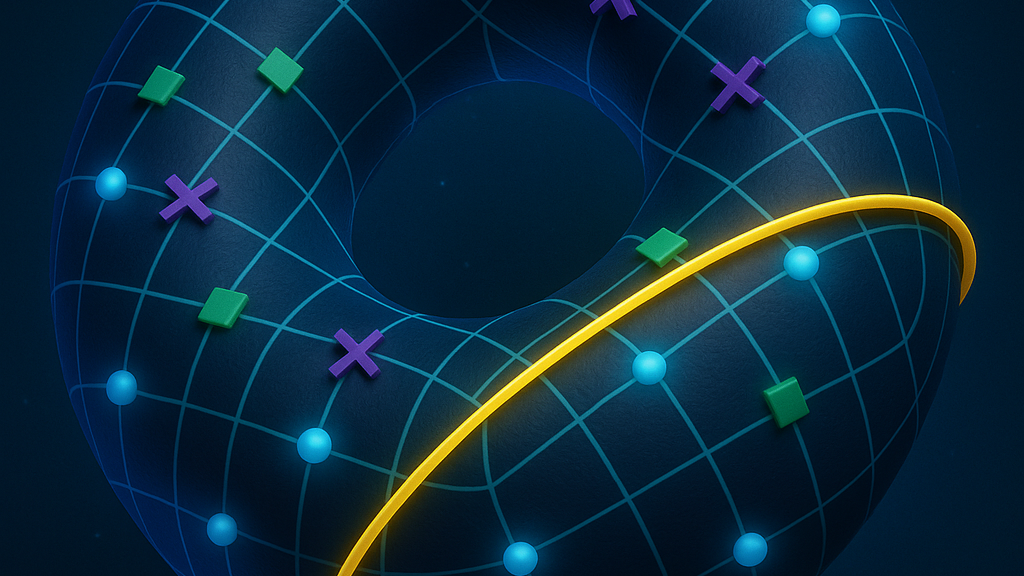

Qubits: These are the fundamental units [quantum particles] that can exist in a superposition of states, meaning they can represent both 0 and 1 simultaneously. This inherent capability allows quantum computers to perform computations on multiple inputs concurrently, leading to potentially exponential increases in processing power compared to classical computers.

Superposition: In quantum mechanics (QM), “the linear combination of two or more state vectors [of quantum particles] is another state vector in the same Hilbert space and describes another state of the system.” Ibid: (p.4)

Entanglement: QM describes a specific kind of superposition which stretches our imagination even further: Entanglement, another key quantum principle, links multiple qubits together in a way that their states are correlated, regardless of the distance between them. This interconnectedness enables faster and more efficient problem-solving for certain algorithms. Ibid: (p.6)

Quantum Gates: These are operations that manipulate the state of qubits, similar to logic gates in classical computing. Quantum gates allow for the creation and manipulation of superposition and entanglement [of the quantum particles], crucial for quantum computation.

Quantum Algorithms: A quantum algorithm is a set of instructions designed to be executed on a quantum computer. It leverages the principles of quantum mechanics, such as superposition and entanglement, to solve certain problems more efficiently than classical algorithms. Quantum algorithms are characterized by their use of these quantum phenomena to perform computations. They are always reversable and offer greater efficiency over classical computer algorithms.

Quantum Circuits: These are sequences of quantum gates applied to qubits, encoding quantum algorithms designed to solve specific problems.

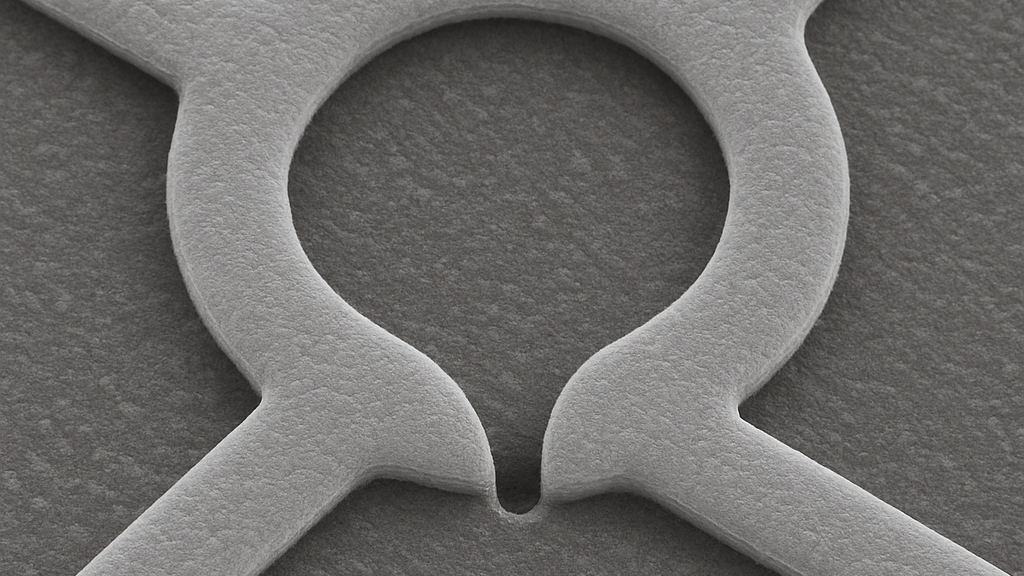

Quantum Processing Unit (QPU): This is the central component that executes quantum algorithms by processing qubits through quantum gates. QPUs can be built using various technologies, such as superconducting qubits, trapped ions, or photonic chips.

Hidary’s work, including his book “Quantum Computing: An Applied Approach,” integrates the theoretical foundations of quantum computing with a hands-on coding approach, focusing on how these systems are built and programmed. He emphasizes the practical aspects of quantum computing, including its applications in fields like drug discovery where quantum computing, combined with AI, can revolutionize the process by enabling the generation of data from quantum equations to train AI models. This approach, referred to as Large Quantitative Models (LQM), allows researchers to explore numerous molecular variations for potentially faster drug development.

Ultimately, according to Hidary, the constitution of a quantum computer is rooted in its ability to leverage fundamental quantum mechanical principles like superposition and entanglement, combined with specialized hardware like qubits, quantum gates, and QPUs, to perform computations unattainable by classical computers.

Quantum Physics or Quantum Mechanics (QM)

In quantum physics, matter is defined as a particle, but can also be defined as a wave. The University of Waterloo has a great website that explains quantum physics is a straightforward way. Quantum Mechanics provides a mathematical method to describe the atomic world precisely. Early on, even physicists that were discovering the quantum nature of the atomic universe had problems accepting the truths quantum mechanics were telling us. We can recall the famous quote from Albert Einstein wrote to Niels Bohr “God does not play dice with the universe” about having to use probabilistic mathematics to describe the link to our observable universe. Quoted from Albert’s letter, “[t]he theory produces a good deal but hardly brings us closer to the secret of the Old One. I am at all events convinced that He does not play dice.” [Britannica] Albert was wrong about this point about quantum mechanics. Quantum computing uses the developed mathematics of QM to express the nature of qubits.

Some basics of quantum mechanics:

- The two golden rules of quantum mechanics

- Wave-particle duality

- Quantum Superposition

- Interference

- Quantum measurement

- Quantization

- Tunnelling

- Decoherence

- Entanglement

The University of Waterloo provides a greater explanation than I do here but the basics are given below.

The two golden rules of quantum mechanics

Rule 1: a particle can be in quantum superposition where it behaves as though it is both here and there.

Rule 2: When measured, the particle will be found either here or there.

Wave-Particle Duality

Most of us have performed or seen the experiment called the double slit light diffraction test in school. Light can only be emitted in single quanta of energy; a particle called a photon. So, how does the constructive and destructive interference patterns that look like waves appear on the wall? The nature of the wave-particle duality is explained by quantum mechanics through a wavefunction. The wavefunction is a wave of probability. Understanding wavefunctions helps us understand the random nature of the atomic world.

Quantum Superposition

Superposition is a property of waves that says if we add waves together, we get another, new wave. Because quantum particles have a wave-like nature, they can be in a quantum superposition or different states. Qbits are two separate particles of matter, photon, electron, or other matter that when paired they can be in any state of position until they are measured. Then they are either “up” or “down”.

Applications:

- Quantum computing: Superposition enables quantum computers to perform calculations faster and more efficiently than classical computers.

- Quantum cryptography: Superposition can be used to create secure communication channels.

- Quantum sensors: Superposition can be used to create highly sensitive sensors.

- Quantum materials: Superposition plays a role in the behavior of certain materials, like superconductors.

Interference

Interference happens when two or more waves intersect. When throwing two pebbles into a pond the waves from each radiate out from the impact points. As the waves intersect you will see the waves add or subtract at the intersections of the wave. The qubit of two particles will interfere with each other to add or subtract where we can form the states of the qubit |0⟩ or |1⟩.

The Language of Quantum Mechanics and Quantum Computing

The language we use for quantum mechanics and Quantum computing is tensor (tensors are used in AI to perform mathematical operations) and tensor’s (vectors are a subset of tensors used in AI/Tensor flow Processors powering neural network deep-learning) mathematical formalism. This mathematical formalism uses mainly a part of functional analysis, especially Hilbert spaces, which are a part of linear space. Such are distinguished from mathematical formalisms for physics theories developed prior to the early 1900s by the use of abstract mathematical structures, such as infinite-dimensional Hilbert spaces (L2 space mainly), and operators on these spaces. In brief, values of physical observables such as energy and momentum were no longer considered as values of functions on phase space, but as eigenvalues; more precisely as spectral values of linear operators in Hilbert space. The best book for understanding the application of mathematics to quantum physics is “Symmetries in Quantum Mechanics: From Angular Momentum to Supersymmetry” Masud Chaichian & Rolf Hagedorn, published by CRC Press, and Copy Righted in 1998 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC.

Notational Use in Quantum Mechanics and QCs

Dirac notation (named after Paul A.M. Dirac an English mathematician and theoretical physicist), also known as bra-ket notation, is a powerful and concise way to represent quantum states and operations in quantum computing and mechanics. It simplifies calculations and provides a clear way to express quantum states, measurements, and operations.

Here’s a breakdown of Dirac notation:

Kets (|⟩):

- Kets represent quantum states, often denoted as |ψ⟩, |0⟩, |1⟩, etc.

- They are used to describe the possible states of a quantum system, such as a qubit.

- For example, |0⟩ represents the “zero” state of a qubit, and |1⟩ represents the “one” state.

Bravs (⟨|):

- Bravs are the complex conjugate transposes of Kets, often denoted as ⟨ψ|.

- They are used to represent the measurement or observation of a quantum state.

- For example, ⟨0| measures the probability of finding the system in the |0⟩ state.

Inner Product (⟨ψ|χ⟩):

- The inner product (⟨ψ|χ⟩) represents the overlap between two quantum states, |ψ⟩ and |χ⟩.

- It’s a complex number that quantifies the correlation or entanglement between the two states.

- The squared magnitude of the inner product, |⟨ψ|χ⟩|², gives the probability of transitioning from state |ψ⟩to state |χ⟩.

Operators:

- Operators are denoted by a hat (e.g., ˆA) and represent quantum operations or transformations.

- They act on Kets to change the state of the system.

- Examples include Pauli gates (X, Y, Z) and the Hadamard gate.

Example:

- A qubit in a superposition state can be represented as α|0⟩ + β|1⟩, where α and β are complex numbers (probability amplitudes).

- Measuring the qubit will collapse it into either |0⟩ with probability |α|², or |1⟩ with probability |β|².

Quantum Measurements

In the quantum world, we can’t always measure the same object in multiple ways. We can only precisely measure the position of an electron if we ignore its momentum. This is called the uncertainty principle. This describes how measuring one property of a quantum particle inevitably disturbs another. In the quantum world, we can measure a particle only with another particle. If we measure an electron with a photon, we exchange a quanta of energy of the electron and change its energy state.

Quantization

Quantization refers to the fact that only certain discrete values of a property are allowed. Quantization of quantum properties is a consequence of the wave-like nature of particles. The properties of confined quantum particles, such as their energy, are limited to discrete or quanta values that could otherwise be continuous. When we look at the spectrum of a neon lamp we see distinct lines of color. The emission of the quantized light shown in the lines are caused by the changes in states of the electrons in “orbit” around the atomic nucleus. We use these spectrum graphs to identify the elements in other suns and planets. We have also learned what different molecules spectrums look like and will tell us the kind of organic gasses or solids exist there.

Decoherence

Unwanted interactions with their surroundings can affect a superposition, causing the state to collapse as if it’s being measured. This is called decoherence. We fight decoherence by isolating quantum particles from their surroundings through cooling or putting them in a vacuum. With quantum computers we cool down to micro-Kalvin temperatures or as close to absolute zero as possible the quantum computer.

Entanglement

Quantum particles can share a special sort of correlation called entanglement, where two particles are so strongly correlated that the properties of one cannot be described without considering the properties of another. The entangled particles are described by a single joint wave function. Entanglement describes a superposition state of multiple quantum particles. While the properties of the electron may be individually highly uncertain, their properties when measured together may be very predictable.

See University of Waterloo website for more detailed information.

This issue was written by guest editor Brent G. Hunsaker, a Senior Staff Engineer at Northrop Grumman with a degree in physics. I appreciate Brent sharing his knowledge and expertise in Bleeding Edge science and technology.