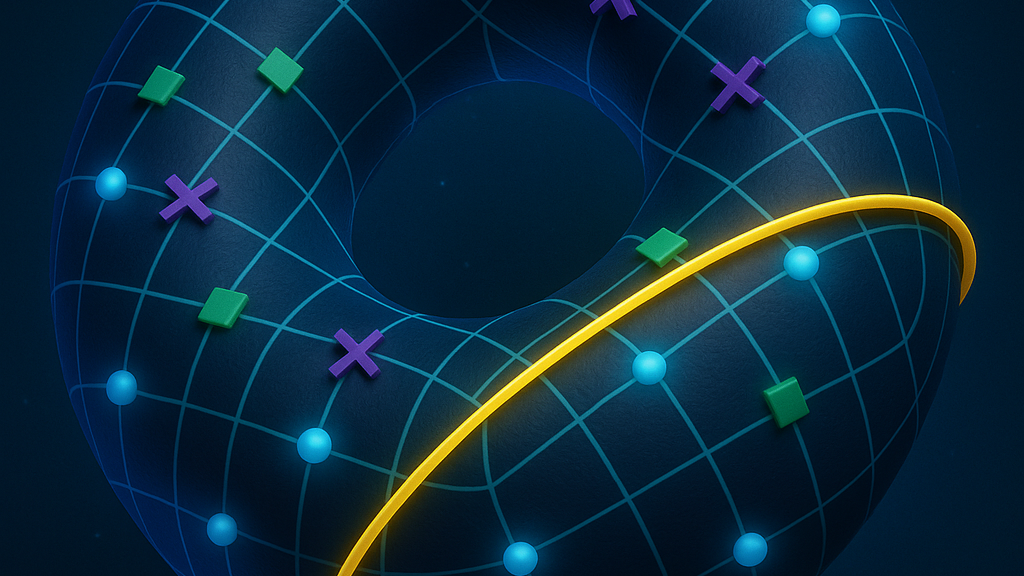

Quantum Computing: Using Surface Codes for Error Correction – Surface & 2D Toric Codes

Surface & 2D Toric Codes

I received a comment from Danny Wall, who also provided his paper on surface codes. His paper is titled “Quantum Error Correction Integration in ACNN Architectures: Surface Code Integration with ACNN Pooling Layers”. After studying Danny’s excellent article, we felt that he raised a good point and that a review of surface codes was in order. What are surface codes and how do they work to improve the accuracy (or if you are familiar with metrology, the system uncertainty)? We address this question in this article. But first, we will have a short discussion on the sources of errors and the approach of surface codes to reducing the quantum computing system uncertainties. We are also providing a link to Danny’s article https://oaqlabs.com/2025/08/15/quantum-error-correction-integration-in-qcnn-architectures-surface-code-integration-with-qcnn-pooling-layers/

Sources of Errors

Thermal Noise

Thermal noise is one of the big challenges in qubit measurements, especially since qubits must operate at millikelvin temperatures where even tiny amounts of thermal energy can cause errors. Here’s a breakdown of the main thermal noise–related errors in qubit readout.

1. Thermal Excitations of Qubits

- Even when cooled close to absolute zero, residual thermal photons can excite a qubit from the ground state ∣0⟩ to the excited state ∣1⟩.

- This leads to thermal population errors, where the qubit state is not purely initialized before measurement, reducing readout fidelity.

- In superconducting qubits, for example, a few parts per thousand thermal occupation (the probability that a qubit is in an excited state due to thermal energy) can already limit measurement accuracy.

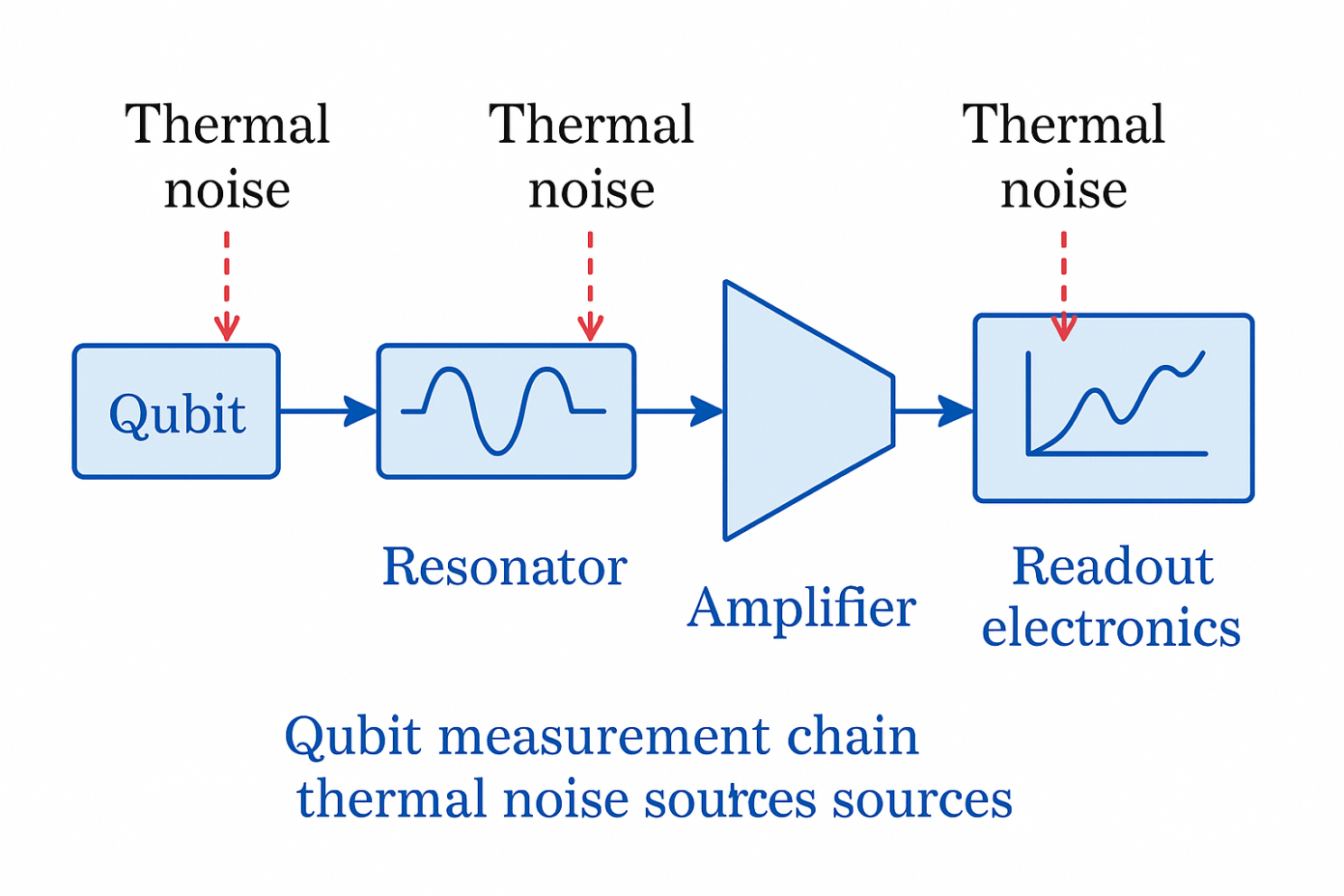

2. Amplifier Noise

- Qubit measurements usually involve weak microwave signals (in superconducting qubits) or photonic detection (in ion/photonic systems).

- To detect these signals, amplifiers are required (e.g., Josephson parametric amplifiers, HEMTs).

- Amplifiers add thermal noise (often near the quantum limit), which blurs the distinction between ∣0⟩ and ∣1⟩ states in the measurement chain.

- Result: increased readout error rate due to overlap of signal distributions.

3. Thermal Photon Shot Noise in Resonators

- Many qubit readout schemes rely on coupling the qubit to a cavity or resonator.

- Suppose the resonator has residual thermal photons (that is, it’s not perfectly in the vacuum state). In that case, these photons can randomly shift the qubit frequency (dephasing), and add fluctuations to the readout signal.

- This produces misclassification errors in measurement.

4. Johnson–Nyquist Noise

- Any resistive element at finite temperature produces broadband voltage/current fluctuations (Johnson noise).

- Even with careful filtering, leakage of this thermal noise into the qubit environment can cause spurious transitions during measurement.

5. Measurement-Induced Heating

- During fast repeated measurements, the detector chain (e.g., cavity + amplifier) may itself heat slightly.

- This raises the effective noise temperature seen by the qubit, again increasing misread probability.

Practical Impact

- For superconducting qubits, thermal noise typically contributes 0.1–1% readout error, which is significant for quantum error correction.

- That’s why labs use: Cryogenic attenuators and isolators, Quantum-limited amplifiers, Extensive filtering of microwave lines, Careful thermal anchoring to dilution refrigerator stages.

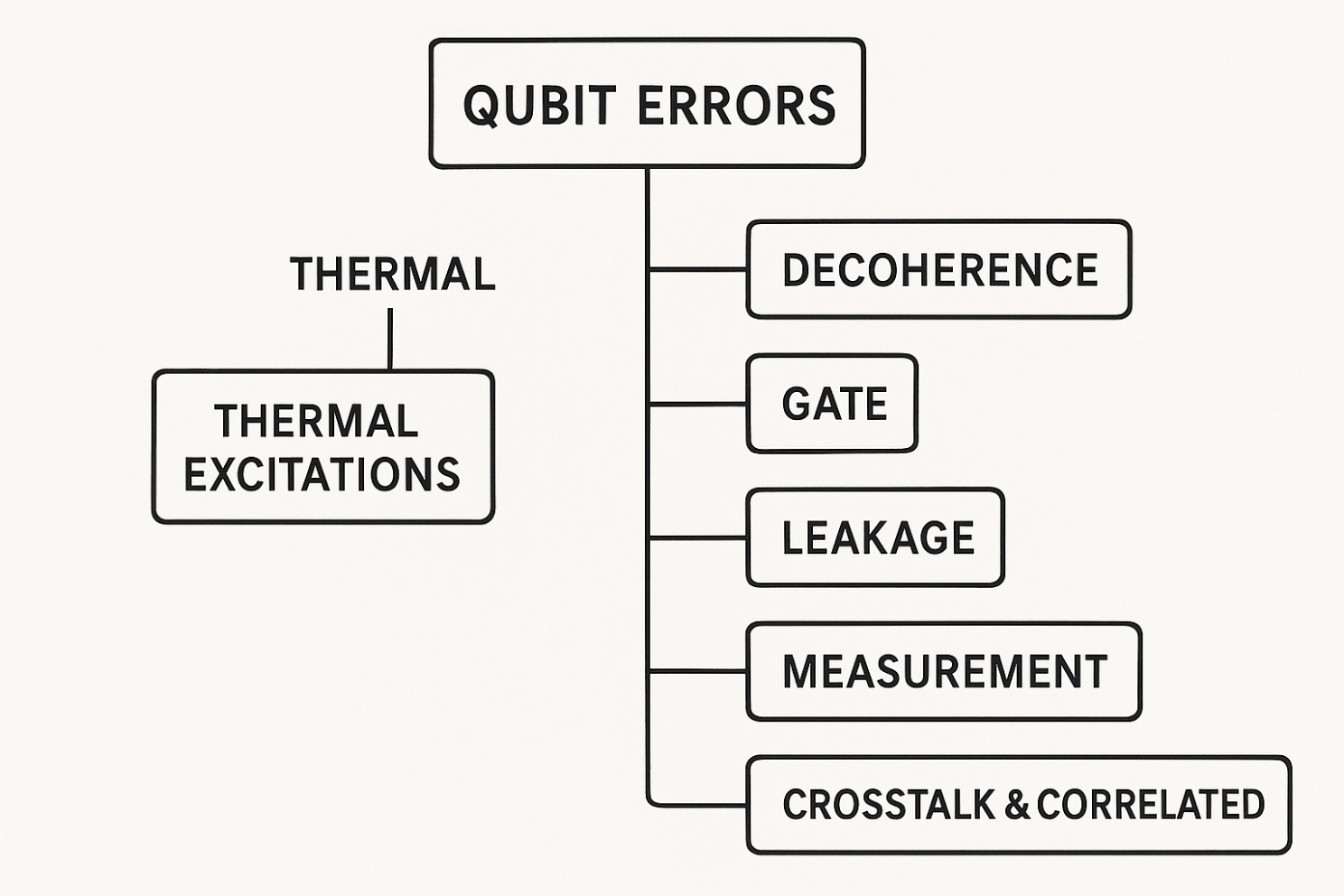

Qubit Errors

Immersing a qubit in a liquid helium bath (or more typically coupling it to a dilution refrigerator stage at millikelvin temperatures) suppresses most thermal excitation errors by drastically reducing the thermal photon population. But other error channels still remain and, in fact, dominate once thermal noise is minimized.

1. Decoherence Errors

- Dephasing (T₂ errors): The relative phase between ∣0⟩ and ∣1⟩ states randomly fluctuates due to environmental noise (flux noise, charge noise, photon shot noise, etc.). This causes loss of quantum coherence without necessarily changing populations.

- Relaxation (T₁ errors): The qubit spontaneously decays from ∣1⟩ → ∣0⟩ by emitting energy into its environment (e.g., electromagnetic modes, substrate phonons). Even at very low temperatures, this “spontaneous emission” channel persists.

2. Gate Errors

- Control pulse imperfections: Microwave or laser pulses may overshoot, undershoot, or have phase/amplitude distortions. This causes over-rotations or under-rotations on the Bloch sphere.

- Cross-talk: Driving one qubit unintentionally affects nearby qubits, introducing correlated gate errors.

- Calibration drift: As hardware drifts over time, pulse shapes and frequencies may deviate from their ideal values, degrading fidelity.

3. Leakage Errors

Many physical qubits (e.g., transmons, trapped ions, Rydberg atoms) are multi-level systems. During operations, the qubit can “leak” into higher states outside the computational subspace (∣2⟩, ∣3⟩…). These are hard to correct with simple error correction codes because the state leaves the qubit space.

4. Measurement Errors

- Even if thermal noise is reduced, the readout chain introduces: Amplifier noise (quantum-limited but not zero). Misclassification due to finite signal-to-noise ratio. Backaction of measurement disturbing neighboring qubits.

5. Crosstalk & Correlated Errors

- Stray couplings (capacitive, inductive, optical) cause unwanted entanglement between qubits.

- Correlated errors (e.g., one photon burst in a resonator affecting multiple qubits) are especially dangerous for error correction since they violate the assumption of independent errors.

6. Fabrication & Material Defects

- Two-level system (TLS) defects in dielectrics, interfaces, or junctions can absorb and release energy, causing both dephasing and relaxation.

- Surface spins, trapped charges, and residual magnetic impurities act as noisy environments.

7. Cosmic Rays & Background Radiation

- Even in cryogenic environments, high-energy particles (cosmic rays, environmental radioactivity) can deposit energy in the chip.

- This creates bursts of quasiparticles in superconducting devices or phonon spikes in ion/semiconductor systems.

- These may lead to rare but catastrophic correlated errors.

After thermal noise suppression (via liquid helium or dilution refrigeration), the dominant qubit errors are decoherence (T₁, T₂), gate control errors, leakage, measurement errors, and correlated crosstalk or radiation events. These are the main limiting factors for reaching the error thresholds required by quantum error correction codes.

Unitary and Arbitrary Errors

The distinction between unitary errors and arbitrary (or non-unitary) errors is central to understanding how qubits fail and how quantum error correction deals with them. Let’s break this down:

1. Unitary Errors

These are coherent, deterministic errors that can be described as the wrong unitary operation being applied to a qubit (or set of qubits).

- Nature: A unitary error doesn’t destroy information; it rotates the quantum state incorrectly on the Bloch sphere.

- Examples: A gate meant to do a Rx(π/2) rotation actually applies Rx(π/2+ϵ).A stray coupling introduces a small unwanted phase rotation. Cross-talk causes a coherent shift in neighboring qubits.

- Mathematical form: If the intended operation is U, but an error happens, the actual operation is U′ = E⋅U, where E is another unitary (like a small over-rotation).

- Impact: They accumulate coherently if repeated — meaning the error can grow linearly with the number of gates.

- Good news: They are, in principle, reversible because they’re coherent. If you can characterize them, you can apply the inverse operation to cancel them.

2. Arbitrary (Non-Unitary) Errors

These are incoherent, stochastic errors — random and not describable by a single unitary. They correspond to interaction with the environment (decoherence, noise).

- Nature: Non-unitary errors lose information into the environment. They can’t simply be “undone” by applying an inverse operation.

- Examples: Bit-flip error: qubit randomly flips from ∣0⟩ to ∣1⟩.Phase-flip error: phase is flipped randomly (∣+⟩→∣−⟩).Amplitude damping: spontaneous decay from excited ∣1⟩ to ground ∣0⟩.Dephasing: random phase kicks due to environment, washing out coherence.

- Mathematical form: Described by a quantum channel (Kraus operators), e.g. instead of a pure unitary UρU†.

- Impact: They accumulate randomly and are often dominant in real systems.

- Bad news: Information lost to the environment cannot be perfectly recovered, only detected and corrected statistically using redundancy (error-correcting codes).

3. Why the Distinction Matters

- Unitary errors are like “wrong but consistent moves” → easier to calibrate out or correct with coherent control.

- Arbitrary errors are like “random accidents” → require quantum error correction codes (surface code, toric code, etc.) to detect and fix.

- Real hardware suffers from both: calibration drift leads to unitary over-rotations, while decoherence leads to arbitrary errors.

To condense these two errors in quantum computing we have:

- Unitary errors = coherent, reversible mis-rotations (control imperfections).

- Arbitrary errors = incoherent, stochastic noise (decoherence, environment).

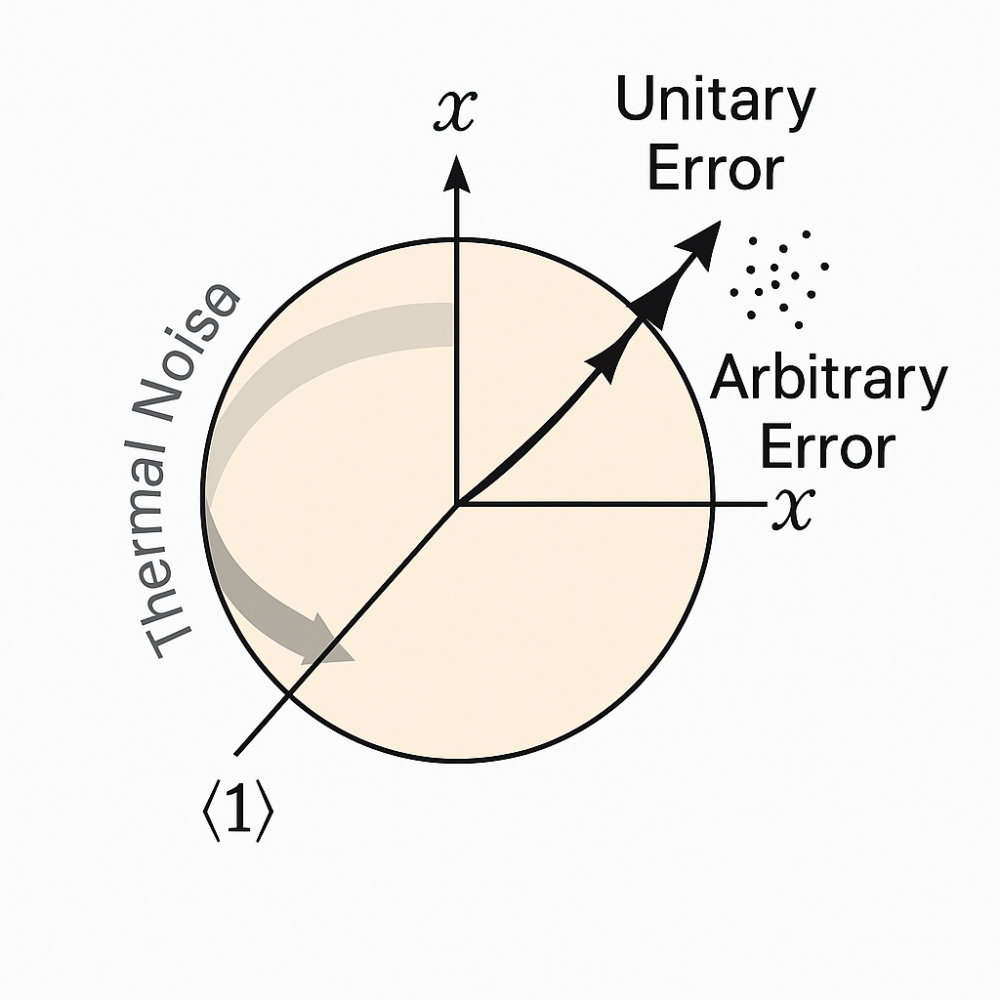

Let me walk you through the Bloch sphere illustration you’re looking at. It compactly shows three main classes of qubit errors all on the same sphere:

1. Unitary Error (Coherent Mis-rotation)

- Depicted as: A black arrow slightly veering off from the intended path.

- Meaning: Instead of rotating the state vector precisely where you want it (say, a π/2 rotation), the control pulse “over-rotates” or “under-rotates.”

- Effect: The qubit ends up at the wrong place on the Bloch sphere — a consistent, reversible error.

- Example: Your gate calibration is slightly off.

2. Arbitrary (Non-Unitary) Error

- Depicted as: A cloud of small black dots spreading out around the intended state vector.

- Meaning: Random noise (like dephasing or amplitude damping) causes the qubit state to wander unpredictably.

- Effect: The state loses its purity — turning from a sharp point into a smeared-out region.

- Example: Phase noise from the environment washing out interference.

3. Thermal Noise Error

- Depicted as: A curved gray arrow between the north pole ∣0⟩ and the south pole ∣1⟩.

- Meaning: Residual thermal excitations cause the qubit to “jump” randomly between ground and excited states.

- Effect: Qubit initialization and measurement are corrupted by unwanted ∣0⟩↔∣1⟩ flips.

- Example: Even in cryogenic setups, a small but nonzero probability exists that a qubit gets thermally excited.

The Big Picture

- Unitary errors = miscalibrations, coherent shifts (fixable with better control).

- Arbitrary errors = random, incoherent decoherence (needs error correction).

- Thermal errors = environment-induced flips between states (needs cooling + filtering).

Together, these cover the dominant error landscape for qubits.